Artists in the Black Collaboration Toolkit – resources for use in Indigenous art projects

Practical resources and best practice information for use in major collaborative arts projects involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island artists.

Background

The Collaboration Toolkit consists of practical resources for people and organisations wanting to develop and participate in collaborative arts projects involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island artists. Its primary focus is the visual arts but the resources can be adapted for use in a range of creative projects. It facilitates effective and ethical management of the various legal and ICIP issues involved, including appropriate protocols and procedures, and best practice agreements.

The Toolkit can be used by people and organisations wanting to develop and participate in collaborative arts projects including:

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island community art centres;

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island artists with independent creative practices;

- non-Indigenous artists;

- arts organisations whether working in the visual arts or in other areas of creative practice (performance, film etc);

- public exhibiting institutions;

- academic institutions; and

- other commercial enterprises .

Some examples of collaborative projects where the Toolkit can add value include:

- major exhibition projects involving the development of a new body of work over an extended period of time;

- collaborative work created at artists’ camps on country in workshops to learn new techniques, or through collaboration with independent artists working in different media or from different cultural backgrounds;

- new collaborative works developed with non-Indigenous arts organizations from outside the visual arts such as the performing arts;

- public art commissions.

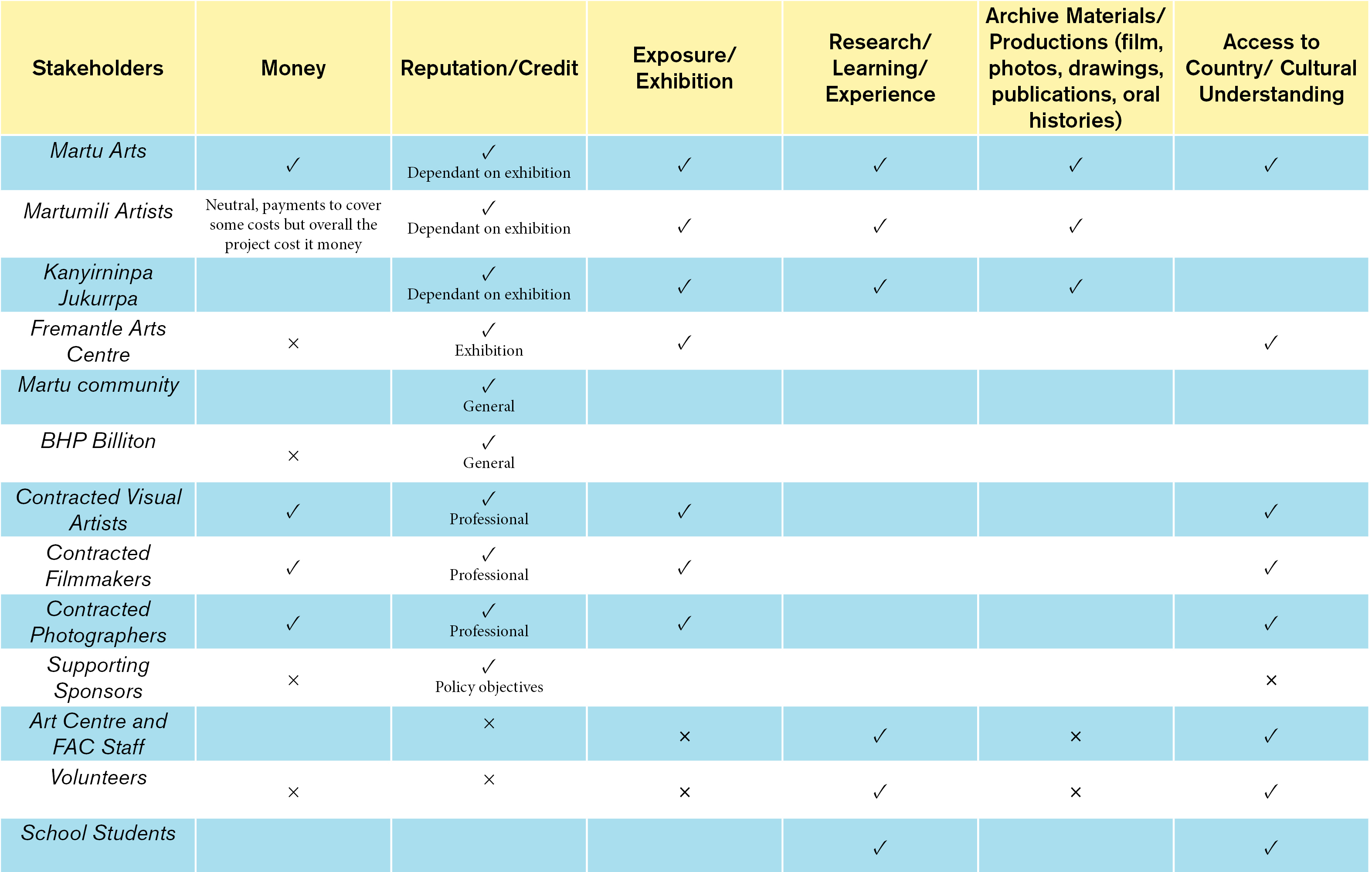

The Value Matrix

As a starting point, the Collaboration Toolkit includes a template ‘value matrix’ to identify the value of the project to all the stakeholders including the Indigenous artists involved and their community. The matrix can be used as a guide in the course of drafting and negotiation of agreements to ensure that the proposed terms secure the intended benefits of the project to these stakeholders.

Case Study: ‘We Don’t Need a Map – a Martu experience of the Western Desert’

The value of this approach is best illustrated by a case study. In 2010, Fremantle Arts Centre, Martumili Artists and the Martu cultural and land management organisation Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa commenced working together on an ambitious collaborative art project ‘We Don’t Need a Map – a Martu experience of the Western Desert’. The project celebrated the lively and enduring culture of the Martu – the traditional owners of a vast area of WA’s Western Desert – but sought to be more than just an exhibition of Martu art – it explored the Martu way of life, the way they cared for country and how they belonged to it. As well as ‘illustrating the distinct contemporary visual language of the Martu’, the exhibition broke down barriers by bringing together Martu and other artists to collaborate and exhibit together. It featured stunning paintings, cutting-edge new media collaborations, animation, finely wrought objects, aerial desert photography, and a public education program of bush tucker and talks with the Martu artists and rangers.

The project culminated in an exhibition at Fremantle Arts Centre which opened in November 2012 and was its single most successful public exhibition with more visitors than any previous exhibition. The Exhibition enjoyed critical success and subsequently secured funding to tour nationally over the next four years through four states.

Funding for the project was principally provided by BHP Billiton, together with a number of government and corporate supporting sponsors.

The value matrix in this Toolkit is based on the experience and input of the stakeholders in this project. It can be used as a template for other projects.

Project Stakeholders – Who are they?

The first step in completion of the matrix is to identify all project stakeholders. This should be much broader than just the parties to a funding agreement or exhibition agreement. It should include all those who will have an interest in the success of the project. In addition to the participating Indigenous artists, other relevant stakeholders may include:

- the artists’ traditional communities;

- if relevant, their community art centres;

- external artists working independently and engaged to collaborate with Indigenous artists;

- supporting art galleries and exhibiting institutions;

- universities examining and researching Indigenous culture;

- commissioning public institutions such as hospitals or local government;

- individual participants – such as curators, art centre managers, workshop facilitators;

- corporate and government sponsors; and

- volunteers.

For the ‘We Don’t Need a Map’ collaborative project, the project stakeholders were identified early on far more broadly than just the funding bodies, the exhibition venue and the artists and included:

- Individual Martu artists who were members of Martumili Artists, a Martu community art centre operated by the Shire of Pilbara;

- Martumili Artists;

- Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa, a non-profit Martu organisation established in 2005 to look after Martu culture and help build sustainable Martu communities ;

- the exhibition venue: Fremantle Arts Centre;

- the broader Martu community;

- External contracted non-Indigenous artists including visual and performance artist and writer Lily Hibberd, photographer Tobias Titz, visual artist Lynette Wallworth and filmmaker Dave Wells;

- Funders and other supporting sponsors including BHP Billiton, the City of Fremantle, CSIRO, the WA Department of Culture and the Arts and Landgate;

- Other staff and specialists employed or contracted by Martumili Artists and Fremantle Art Centre who had direct roles in bringing the project to fruition including curator Erin Coates, art centre manager Gabrielle Sullivan, writer John Carty and animator Sohan Ariel Hayes;

- Volunteers who were critical to enable the creative workshop and artists camps to occur; and

- School students, who would be the focus of the accompanying education program.

How will the project benefit the stakeholders?

The second step is to consider the benefits of the project to each stakeholder. A range of potential outcomes from the project are contemplated in the matrix template, from financial benefits to greater cultural understanding. Outcomes which might be listed in the matrix are described in further detail below. Importantly we are steering away from the legal language of copyright ownership and looking at values more generally. Intellectual property law is only one means to secure the value sought by a stakeholder.

What is important is to consider each stakeholder in turn and examine what their motives are for participating – what value will they be looking for from the project? Too many participants enthusiastically embark on projects having only considered the benefits that they themselves will receive. Understanding the drivers and expectations of the other participants enables the project to be structured in a way that is fair to everyone and reduces the likelihood of disenchantment, disappointment and relationship breakdown when the project doesn’t deliver the expected outcomes. Problems arise in collaborative partnerships when the parties who are supposed to working together are not on the same page and don’t understand what others are hoping to achieve through the collaboration.

A brief description of the more obvious ‘values’ or ‘returns’ that stakeholders might expect to receive is set out below.

Money

Which stakeholders will receive financial benefits? An artist, for example, may be paid to participate or may be entitled to receive proceeds from the sale or licensing of work created for the project (the value matrix shows “Money” as a positive ‘+’ for these stakeholders). Some stakeholders such as corporate sponsors or funding bodies will be providing financial support to the project rather than receiving a financial benefit (negative ‘-‘); however will be looking for other non-monetary outcomes. Some stakeholders may receive payments that are merely to cover or contribute to costs incurred in delivering the project (and the value matrix shows this as neutral ‘~’).

Reputation / Credit

Will the project provide an opportunity to enhance the reputation of a stakeholder? For example, it could create an opportunity for a participating artist to develop his or her professional profile (through an exhibition at an important public venue), or the opportunity for a sponsor to receive public credit for supporting the arts. It may fulfil the policy objectives of a government funder or the research goals of an academic or a university.

Exposure / Audiences

Will the project give the artists and art centres access to new and different audiences through an exhibition or otherwise provide exposure for a stakeholder? Will it bring new audiences into a public gallery?

Research / Learning / Experience

Will the project be a research or learning opportunity? For example, the project may enable Indigenous artists more familiar with traditional painting techniques to work with multimedia artists or animators or other designers to learn new techniques and produce new products, or an Indigenous art centre or arts worker gaining curatorial experience through participation in a large-scale external exhibition. It may have a school education component to engage the broader community.

Increasingly universities with expertise in areas relevant to Indigenous culture (ranging from anthropology to fine art) see the sponsorship of large collaborative exhibition projects as having a synergy with academic and research outcomes. Such projects create opportunities for academic staff to explore Indigenous country with traditional owners and cultural custodians, conduct research into Indigenous stories, cultural sites and culture and, above all, generate opportunities for academic publication. This can be a valuable source of funding for Indigenous artists to travel to traditional country, create new works and exhibit in major public galleries and museums. Such projects invariably generate important sources of documentation to record and protect significant Indigenous cultural histories, performances and knowledge. However, there can be a tension between those opportunities for Indigenous artists and their communities and an academic agenda focussed on ownership of intellectual property and control over publication. This is so even though most academic institutions have carefully managed protocols and procedures to deal with academic research involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island culture. Such protocols can focus more on protecting the institution from any claim that it did not seek cultural approval and securing a broad discretion to publish rather than a genuine engagement with the cultural custodians. The value matrix is useful in highlighting these competing considerations and can generate productive conversations around ways of managing the cultural sensitivities.

Archive Materials / Publications (film, photos, drawings, publications, oral histories)

Will the project result in the creation of materials or archival records that will be useful beyond the life of the project? Who will receive copies of those materials and what are the conditions of use? This is particularly important if such material contains Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP). Our experience is that Indigenous artists and their communities often assume that material which embodies their cultural knowledge is theirs to use and share with their communities. As a matter of law, the intellectual property and copyright ownership may rest with someone outside the community – the author of an academic article or curatorial text, a filmmaker or photographer or a funder who commissioned and paid for the materials to be created.

Identifying these competing expectations early enables protocols to be devised and contractual protections to be agreed which are acceptable to both parties.

Access to Country / Cultural Understanding

Will the project provide an opportunity for artists, elders or other community members to return to their traditional country? Will it otherwise enhance the cultural understanding of other stakeholders? The project may allow Indigenous artists, for example, to undertake bush trips for the purposes of creating work in collaboration with other external artists. The final exhibition may lead to broader community understanding of Indigenous culture.

Other Outcomes

This list is not exhaustive. There may be other important values. Conversely some of the outcomes described above may not be relevant. Each matrix will be tailored to its project.

Case Study: Benefits of We Don’t Need a Map

The ‘We Don’t Need a Map” project provided an opportunity for Martu artists to create new work, to collaborate with external artists to produce works in different media, to raise their professional profile through participation in an exhibition in an important public gallery, and to educate audiences outside their community about Martu life and culture. The project also provided critical funding for the artists to spend time on country to develop new work. On the completion of the touring exhibition, the works will return to the art centre and be available for sale so there is also the prospect that the artist will receive a direct financial benefit.

The project enabled Martumili Artists and Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa to increase awareness of their role within the Martu community, the arts community and the general community. External arts organisations and artists visited the Martu community, and the exhibition provided a vehicle to explain the role of Martumili Artists and Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa to the public. An archive copy of material produced during the project was provided to Martumili Artists. Martumili Artists staff developed new skills working on a major exhibition project.

The independent artists who collaborated with Martu artists were able to raise their professional profiles through the creation of new work and participation in the project exhibition. However for most the single most important outcome was the unique experience of spending time with the Martu on Martu country and gaining a greater understanding of Martu culture.

The project provided an opportunity for the project sponsors to gain a greater understanding of Martu art and culture, to fulfil policy and corporate objectives, and to raise their profile in the community.

Through the development of an education program and supporting materials to accompany the exhibition, school students were able to gain a greater understanding of the Martu community and its art.

Using the Value Matrix

Understanding the ways in which the interests and motivations of the stakeholders intersected and overlapped right from its inception enabled the We Don’t Need a Map project to be managed and documented in a way that facilitated a best practice approach to respecting the contribution of each stakeholder. Crucially it highlighted the importance of respecting the cultural protocols of the Martu which lead to a level of consultation and acknowledgement which was a cornerstone of the project and directly contributed to its success.

Arts Law suggests that all parties engaged in the project have input into the value matrix which is then used as a springboard for discussion about the structure of the project. It becomes a checklist and reference document for t5hose tasked with drafting the Memorandum of Understanding, or Heads of Agreement or other contracts.

Template Agreements

The Collaboration Toolkit includes a range of template agreements that can be used to manage the various legal and Indigenous cultural and intellectual property (ICIP) issues which arise in collaborative art projects involving Indigenous artists. The agreements are suitable for a range of different types of collaborative art projects and could provide a useful starting point when drafting agreements for other types of collaborative projects. Each of these sample agreements reflects the principles enshrined in the Australia Council’s protocols for working with Indigenous artists and represents best practice in dealing with Indigenous Intellectual Property. Each agreement reflects the experience of art centres, artists and institutions who have either consulted us or shared with us the issues they faced in undertaking such projects in the past and seeks to strike a fair balance between the interests and priorities of all the parties involved.

Collaboration Agreement: Visiting Artist

This sample Collaboration Agreement should be used when an external non-Indigenous artist is invited to an Indigenous community art centre to work collaboratively with the art centre’s member artists to create a body of work. The existing skills and artistic practices of the visiting artist are combined with the skills and artistic practices and cultural traditions of the local artists to create new works in collaboration. In this sample agreement, the visiting artist is paid for his or her contribution and the resulting works are owned by either by the art centre or by its member artists subject to the terms of their art centre membership agreements. In other words, the resulting works are held by the art centre for exhibition and sale. The agreement is drafted to present two options insofar as the intellectual property (copyright) of the artworks is concerned – either joint ownership of the copyright by the visiting artist and the local artists or a complete assignment of all copyright to the local artists. What is appropriate will depend on factors such as the amount of the payment to the visiting artist, the degree of creative contribution and whether there is ICIP in the resulting works. It makes clear that the visiting artist retains all pre-existing intellectual property rights. There are clauses dealing with how and when the visiting artist will be credited, the use the visiting artist may make of the work in his or her portfolio, insurance and moral rights. The agreement sets out the visiting artist’s responsibilities and standards of conduct when visiting a remote Indigenous community and provides a process for the art centre to communicate clearly any relevant protocols or policies around photography, and social media.

Collaboration Project: Project Facilitator Contract

Collaborative Indigenous art projects often involve a large number of people working with artists in different roles. It’s important that there is a contract in place with anyone who is working externally to the art centre or organization with overall responsibility for the project. This sample agreement can be used when contracting an external person or arts business to facilitate a part of the creative project whether through running workshops, or mentoring the creative process or otherwise. It could be adapted for use in contracting a curator for the project. It is not suitable to govern the relationship between the individual Indigenous artists creating the work and the organization with overall responsibility. It is also not suitable for the situation where the contractor is not a facilitator but a true co-creator – an artist who is working jointly with the local Indigenous artists to create a collaborative piece.

Collaboration Project: Indigenous Art Centre, Artist and Exhibiting Institution Agreement

This sample agreement can be used when an art centre is working with an exhibiting institution and an external artist or creative organization (whether in the visual arts sector or another creative medium) to create a new body of work for a major public exhibition. It is intended to regulate the overarching collaboration between these three principal players. It is not suitable for particular individuals or businesses who are contracted to work on pieces of the project such as a filmmaker documenting part of the process or a person running an artist workshop. In that situation, Arts Law’s Project Facilitator Agreement is more suitable.

It is also not suitable for the situation where the exhibiting institution is not involved in the project from the outset as an equal partner. If the art centre is engaging or contracting an external artist to work jointly with the local Indigenous artists to create a collaborative piece or pieces (which may or may not later be exhibited) Arts Law’s sample Collaboration Agreement: Visiting Artist is more suitable.

Volunteer Deed of Release

Volunteers play an important role in nearly every collaborative art project whether making films, organising festivals or putting on a major exhibition. A written agreement is important to ensure the volunteer understands his or her responsibilities and the policies and protocols that must be respected. This is particularly important if the volunteer will be working with Aboriginal or Torres Strait Island creators or communities. This sample Volunteer Agreement is designed as a simple letter to be sent by the person or organisation responsible for the project to the volunteer. It includes terms dealing with ownership of intellectual property created by the volunteer, insurance and how certain costs and expenses are reimbursed.

Need more help?

Useful Readings

- Arts Law Centre of Australia, Information Sheets:

- Australian Copyright Council Information Sheets, available at www.copyright.org.au

Contact Arts Law if you have questions about any of the topics discussed above.

Telephone: (02) 9356 2566 or toll-free outside Sydney 1800 221 457

Also visit the Artists in the Black website (www.aitb.com.au) for the latest news about the service.

Disclaimer

The information in this information sheet is general. It does not constitute, and should be not relied on as, legal advice. The Arts Law Centre of Australia (Arts Law) recommends seeking advice from a qualified lawyer on the legal issues affecting you before acting on any legal matter.

While Arts Law tries to ensure that the content of this information sheet is accurate, adequate or complete, it does not represent or warrant its accuracy, adequacy or completeness. Arts Law is not responsible for any loss suffered as a result of or in relation to the use of this information sheet. To the extent permitted by law, Arts Law excludes any liability, including any liability for negligence, for any loss, including indirect or consequential damages arising from or in relation to the use of this information sheet.

© Arts Law Centre of Australia

You may photocopy this information sheet for a non-profit purpose, provided you copy all of it, and you do not alter it in any way. Check you have the most recent version by contacting us on (02) 9356 2566 or tollfree outside Sydney on 1800 221 457.

The Arts Law Centre of Australia has been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.