David Beaumont Case Study – Do I need permission to use this old photo in my work?

David Beaumont is a Melbourne based visual artist whose works are held in private collections in Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom. He is a five time finalist in the ANL Maritime Art Prize and has exhibited in over a dozen solo exhibitions since 1999. In late 2010, he contacted Arts Law regarding an exhibition he was in the process of creating which addressed the controversial and highly emotional theme of terminal illness and euthanasia.

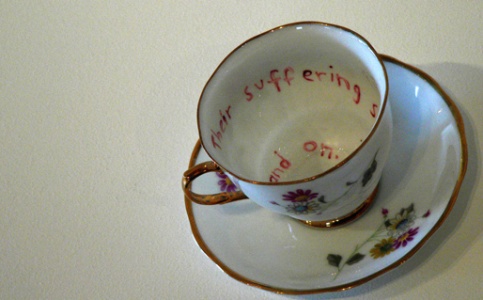

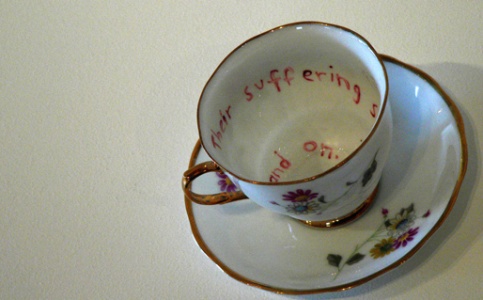

David planned to exhibit 11 works, 9 of which incorporated old photographs purchased at local antique stores of unidentified people. He did not plan on manipulating the photographs in any way, but wished to add text and other objects to create ‘installation’ style works conveying a new and unique message. David was not seeking to promote any particular view on euthanasia but rather to heighten community awareness of euthanasia by exploring the theme in a general way.

David wanted to understand the legal issues arising from his use of the old photos of unknown people. Firstly, David wanted to know whether the photos were subject to copyright which prevented him using them. Secondly, he wanted to know whether the people in the photos or their families could sue him for defamation because of the themes of his artwork. Arts Law referred the matter to lawyer Matt Vitins of Allens Arthur Robinson for telephone advice.

Copyright in photographs taken before 1 May 1969 endures for 50 years from the end of the calendar year in which the photograph was taken. This means that copyright has expired in all photos taken before 1960. Based on his examination of the photos, David was confident that they were all from the early 1950s or even earlier. If so, the photos were all in the public domain and he could use and reproduce them without infringing copyright. If the photos had been more recent, he would have needed to consider whether the way he was using them required him to seek the permission of the copyright owner (usually the photographer). This would have been very difficult given he had no idea who that might have been.

In relation to the issue of defamation, David was concerned that his artworks could be interpreted as suggesting that the people in the photos had a particular view on death or dying and that this could be defamatory. This risk was assessed at quite low for a number of reasons. First, given the age of the photos, it was likely that a number of the people shown in the photos were likely to have passed away. It is not possible to defame a deceased person. Secondly, although some of the people depicted might be living, the artworks did not name them (and in fact David did not know who they were) and the risk that they might be recognized was considered to be quite low. Thirdly, most people would understand the artworks to reflect the ideas of the artist rather than any person in a photo comprising part of the work. Nevertheless Matt suggested that David include a disclaimer at the exhibition stating that the persons depicted in the photographs had not endorsed any message or statement sought to be communicated by the artist in the artwork and that any facts suggested by the photographs were fictional.

David did include a disclaimer and successfully showed his “Eu thanotos” exhibition at the Geelong Gallery in Victoria.

David’s case illustrates the importance of artists thinking about copyright ownership if their work is going to incorporate or reproduce photos taken by others.